From the web of the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), a towering genius in the history of Western art, is the subject of this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition. During his long life, Michelangelo was celebrated for the excellence of his disegno, the power of drawing and invention that provided the foundation for all the arts. For his mastery of drawing, design, sculpture, painting, and architecture, he was called Il Divino ("the divine one") by his contemporaries. His powerful imagery and dazzling technical virtuosity transported viewers and imbued all of his works with a staggering force that continues to enthrall us today.

This exhibition presents a stunning range and number of works by the artist: 133 of his drawings, three of his marble sculptures, his earliest painting, his wood architectural model for a chapel vault, as well as a substantial body of complementary works by other artists for comparison and context. Among the extraordinary international loans are the complete series of masterpiece drawings he created for his friend Tommaso de' Cavalieri and a monumental cartoon for his last fresco in the Vatican Palace. Selected from 50 public and private collections in the United States and Europe, the exhibition examines Michelangelo's rich legacy as a supreme draftsman and designer.

And I say: The exhibition is extraordinary and I will present in this post, the most relevant pictures that I took during my visit.

Please press over the pictures that I present in this blog, to make them bigger and so that you can be able to read the notations which the museum included in the presentation.

Please press over the pictures that I present in this blog, to make them bigger and so that you can be able to read the notations which the museum included in the presentation.

|

| Greek: Late 4th century BC. Michelangelo would have studied the movements of Hellenistic sculptures like this, to sculpt his archer below. |

Please refer to the Metropolitan Museum web, to find the pictures presented during the following interview.

Language of a Genius—Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer with Author Carmen C. Bambach

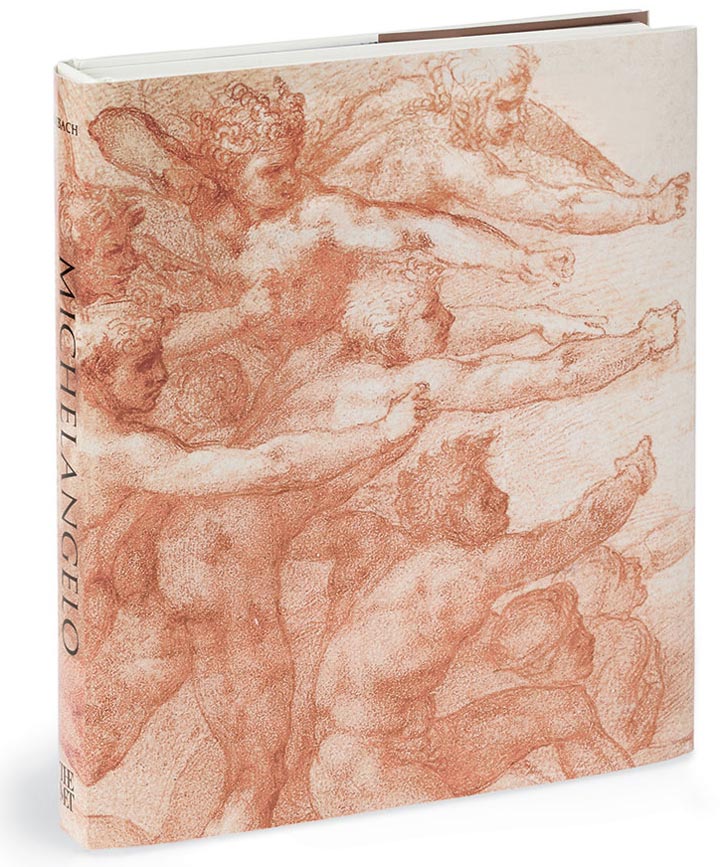

Consummate sculptor, painter, architect, and draftsman Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) was celebrated for his disegno, a term that embraces both drawing and conceptual design. In Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer—which accompanies the eponymous exhibition on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 12, 2018—author Carmen C. Bambach presents a comprehensive and engaging narrative of the artist's long career.

Consummate sculptor, painter, architect, and draftsman Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) was celebrated for his disegno, a term that embraces both drawing and conceptual design. In Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer—which accompanies the eponymous exhibition on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 12, 2018—author Carmen C. Bambach presents a comprehensive and engaging narrative of the artist's long career.

Left: Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer by Carmen C. Bambach, featuring 241 full-color illustrations, is available at The Met Store andMetPublications.

Named one of the best art books of 2017 by the New York Times, this catalogue relates Michelangelo's drawings to his major commissions—such as the ceiling frescoes and the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, the church of San Lorenzo, and Saint Peter's Basilica—offering fresh insights into the Renaissance master's creative process. I recently spoke with Carmen about disegno, the power of drawings, and Michelangelo's savvy shaping of his own history.

Rachel High: This catalogue focuses on Michelangelo's disegno. Could you explain that term and why it is so important to understanding Michelangelo in the context of his time?

Carmen C. Bambach: This one term embraces everything from the concrete to the conceptual; it unifies the process of drawing on paper and the process of inspiration. Disegno gives you a continuity among mind, eye, and hand. For that reason, it's a very useful term to describe Michelangelo. One of the reasons I wanted the title Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer was because when Vasari wrote the second edition of his biography of Michelangelo's life in 1568, he pronounced Michelangelo the culmination of all of the history of art because of his command of disegno.

Right: This sketch shows Michelangelo's command of disegno. Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Sketches of the Virgin, the Christ Child Reclining on a Cushion, and Other Sketches of Infants. Pen and brown ink, 11 1/8 x 8 1/4 in. (28.2 x 21 cm). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett (KdZ 1363)

One of the most difficult things for us today is to try to see Michelangelo in the intellectual culture of his time. Michelangelo was a sculptor, a painter, and an architect. The word "design" in English is not perfect, but design, in a profound sense, is the artistic idea. One of the things I wanted to accomplish with the book and the exhibition was to try to recover this much more all-encompassing term—disegno in the Italian sense—which was the way Michelangelo's practice was seen in his time.

Rachel High: The book includes many preparatory drawing for some of Michelangelo's most well-known masterpieces such as the works in the Sistine Chapel. What do these drawings reveal about his process?

Carmen C. Bambach: We can admire the Last Judgment or the tomb of Julius II as final products, but these works are missing the germination of ideas, invention, and the proximity to his mind, hand, and genius. Without the drawings, you have all these milestones with no connecting threads. I see Michelangelo's approach to drawing as a language. One captures much of the artist's thinking on the paper. It is very immediate and spontaneous.

Other books about Michelangelo's drawings focus on just the works on paper, but, to me, it was so much more about the scope of his creativity. I felt it was really important to look at a large variety of drawings—not only sketches that are very spontaneous and small, but also figure studies, life drawings, full-scale drawings, and cartoons. It was also important to examine the kinds of artists that Michelangelo had as collaborators.

I tend to call them surrogate artists, because to say that Michelangelo was collaborating with somebody was not the way he saw it. He was very possessive of his design ideas, and just delegated the work of execution to others. For example, Michelangelo considered himself exclusively a marble sculptor, but rather than saying no to a very monumental bronze equestrian sculpture commissioned by the queen of France, Michelangelo passed it on to a surrogate artist. There is a very tangible business side to Michelangelo; he died a rich man. Even in passing off his commissions to other people it is clear that he made some money. I think the concept of disegno is at the very heart of all of this, because it begins to explain the separation of artistic idea from manual execution.

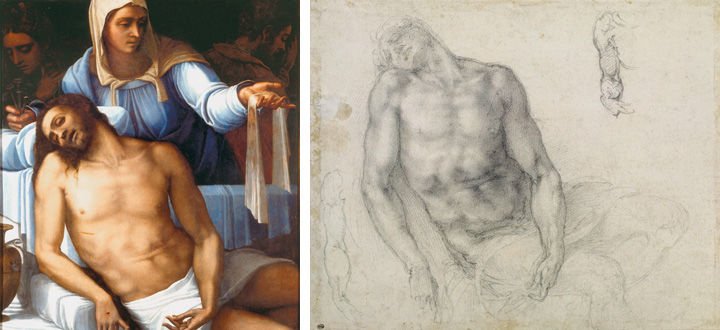

Michelangelo formed mutually beneficial relationships with surrogate artists who would use his drawings as the basis for paintings. Left: Sebastiano del Piombo (Italian, 1485–1547). Pietà. Oil on slate, 48 13/16 x 43 3/4 in. (124 x 111.1 cm). Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, Seville, on loan to the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Right: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Studies for Christ in the Pietà of Úbeda for Sebastiano del Piombo. Black chalk, 10 x 12 9/16 in. (25.4 x 31.9 cm). Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques, Paris (716)

Michelangelo's relationship with collaborator Sebastiano del Piombo was especially complex. While Michelangelo was living in Florence doing all the great sculptural projects, Raphael had become the favorite of the Pope in Rome. Michelangelo needed a surrogate painter who could compete with Raphael, and he found this in Sebastiano. Michelangelo gave him drawings to help him come up with compositions for altarpieces that could compete with Raphael. In many ways Sebastiano succeeded well enough, though he could not overshadow Raphael.

The friendship between Sebastiano and Michelangelo broke off at the time of the Last Judgment (1533-34). Sebastiano, who was very keen on experimenting with media, wanted Michelangelo to paint the Last Judgement in oil paint. Emboldened by their friendship, Sebastiano went ahead and actually got the wall coated for an oil mixture, and Michelangelo obviously threw a fit. Sebastiano died in 1547, completely unforgiven by Michelangelo.

Rachel High: In the second chapter of the book, you note that through his biographers, Michelangelo downplayed influences of late 15th-century Florentine art and emphasized associations with classical sculpture and early Italian art. How did Michelangelo shape his own legacy, and how does that factor into how we perceive him today?

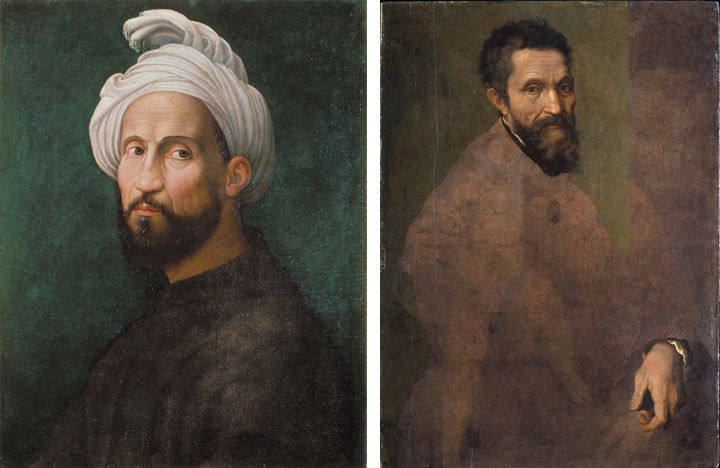

Carmen C. Bambach: Michelangelo constructed his persona as an artist. By about 1530 he stops signing "Michelangelo scultore," and just used "Michelangelo." Many aspects of his identity started changing toward the end of the Last Judgement, when he met Vittoria Colonna. He apparently cleaned himself up, bought new clothing, and cultivated the manners of a gentleman. This is interesting because of how physical marble carving is. There are portraits of Michelangelo wearing a turban to catch sweat and marble dust, but that kind of portrait only exists before the 1530s. After that you see him dressed like a nice gentleman in black velvet, so he really did a great deal to refine his biography.

These two portraits show the change in how Michelangelo presented himself as he advanced in his career. Left: Giuliano Bugiardini (Italian, 1476–1555). Portrait of Michelangelo. Oil on canvas, 217/8 x 171/8 in. (55.5 x 43.5 cm). Casa Buonarroti, Florence. Right: Attributed to Jacopino del Conte (Italian, 1510–1598). Portrait of Michelangelo (1475–1564), ca. 1544. Oil on wood, 34 3/4 x 25 1/4 in. (88.3 x 64.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Clarence Dillon, 1977 (1977.384.1)

Michelangelo's affection for Vittoria Colonna, which came very late in his life, was a completely platonic affection. Even during his time there was quite an extraordinary reframing of Michelangelo's love for beautiful, young, aristocratic men. Michelangelo gave them gifts of drawings and the book discusses this pretty openly. I felt that this part of his activity and biography really needed to be discussed again in terms that are closer to the historical truth. There was so much purging of that subject; the first time Michelangelo's poetry was published, his grand-nephew changed the pronouns, so that uses of "he" became "she."

Left: Michelangelo gifted drawings like this one to his beloved male companions. Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi. Black chalk, with losses on the design surface delicately integrated with brush and gray wash, 16 1/8 x 11 3/8 in. (41 x 29 cm). The British Museum, London (PD 1895,0915.519)

Left: Michelangelo gifted drawings like this one to his beloved male companions. Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi. Black chalk, with losses on the design surface delicately integrated with brush and gray wash, 16 1/8 x 11 3/8 in. (41 x 29 cm). The British Museum, London (PD 1895,0915.519)

Ascanio Condivi's biography of the artist proudly states in the preface that the book is "from the living oracle." This is the authorized biography or maybe even the autobiography of Michelangelo, and there are aspects of it that are clearly constructed. Condivi spends considerable time asserting that Michelangelo was not really a miser, but in fact was very generous and had many friends.

Biographies themselves are constructs. There is an area for invention or, at least, shaping the historical reality. This is an age-old method that is not just unique to Michelangelo. We are not by any means looking at the complete picture of Michelangelo's production as a draftsman. He burned drawings several times and was very secretive about his practice. He clearly edited his oeuvre; there is this element of shaping in the persona of the disegnatore. For example, theorists of the 16th century tended to praise pen-and-ink drawings the most, so what do we have of his early period? The pen-and-ink drawings. It is a very curated beginning.

Rachel High: For many people, Michelangelo and the 15th and 16th centuries might feel very far away. How do you hope this book will help readers connect to the past and understand this artist?

Carmen C. Bambach: All the surviving letters by Michelangelo give scholars a unique opportunity to tell his story through biography; the mountains of letters are quoted throughout the book. In modern art history, the biographical approach has been a little bit frowned upon. I feel that this is unjustified; you can't really condemn an entire method. Having so much information about Michelangelo lends itself to this biographical approach. This book isn't romanticized, and much emerges about Michelangelo the man that in many ways explains the art. As a historian, I believe in being close to the evidence. It was important to me for this to read as a narrative. I wanted to bring the reader back to the Renaissance, so they could understand so much about him in the context of his time.